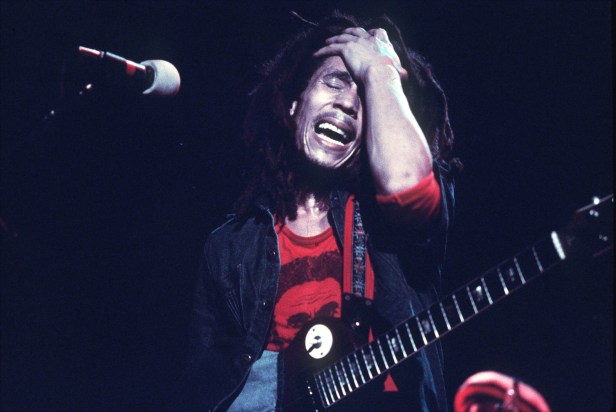

The following is an article from Sound On Sound magazine from September 2005. It interests me because I collect Bob Marley and the Wailers media, including live recorded performances. In the article, the author describes an encounter with Mrs. Rita Marley about the recovery of rare concert recordings from damaged audio tapes. I believe you will find it worth a read.

Baker Man

Sound On Sound September 2005

If you’re unfamiliar with the concept of baking magnetic tape, check out Paul White’s article on the subject from SOS May 1996, or at www.soundonsound.com/sos/1996_articles/may96/salvagearchives.html.

To briefly recap, tape baking is necessary with magnetic recording tape stock of a certain vintage (mid-’70s to early ’80s). In such tapes, the adhesive binding the plastic tape to the magnetic oxide that stores the recorded signal dries out or becomes unstable after a few years. It can then absorb moisture from the air, causing the oxide on the tape to become raised and sticky. If the tape is played back while in this condition, the sticky oxide can be pulled from the tape as it passes through the playback heads, resulting in dropouts and/or the complete destruction of the signal recorded on the tape. However, gentle baking for several days in a special oven designed to produce a carefully controlled, uniform heat can drive the absorbed moisture from the adhesive, rendering the tape playable once again.

Shortly after directing the Copyroom into multitrack transfer work, Kevin Vanbergen began to encounter ‘sticky’ tapes from record companies and members of the public that had to be baked before they could be transferred. At that time, the only tape-baking facility was at the Quantegy (formerly Ampex) tape factory outside Reading, which had been set up by Ampex in the early ’80s when the so-called ‘sticky shed syndrome‘ was first noticed in stocks of the company’s 456 and 406 tape. Kevin recalls: “Ampex felt they had a responsibility to their customers, so they baked tapes for free for a while, but when they noticed that it was happening to other brands of tape as well, they realised it wasn’t necessarily their fault, and handed over reponsibility for baking to this other guy, and started charging for it. I used to send tapes that needed baking to him, but I soon got fed up of sending tapes back and forth to Reading, so I asked Quantegy what kind of oven was required for the job, and we got one here with capacity for about 15 to 20 two-inch tapes. When clients in London realised they didn’t have to ship tapes to Reading any more, our baking business took off, and we bought two more ovens, each with room for about 50 tapes.

“We get phone calls every day about tape baking now, and we often have to explain why it’s needed. There’s a lot of urban myths; I’ve heard even quite well-respected, technical people say ‘Oh, you can bake the tape, but then you get one go at transferring it, and if that doesn’t work, it’ll be lost forever.’ But that’s not the case. It usually makes the tape playable for about 20 or 30 days, during which time you can transfer it. Once we’ve explained this to potential customers, we can either bake the tape and leave the digital transfer to them, or do the whole process for them, in which case the tape baking is free.”

The Copyroom’s tape-baking clients range from members of the public wanting to transfer low-quality audio recordings of late relatives right up to the top names in the recording industry. One day, following a phone call in which the Copyroom were asked if they could help save 50 unspecified tapes, one such ‘name’ client dropped by the FX premises in a stretch limo. It turned out to be none other than Rita Marley, widow of Bob. And she bought a crate with her…

“When we got it open, the tapes were covered in mould — at first I thought they were mould. They’d been stored in a hot garage in Jamaica. Moisture’s bad, but at least you can bake that away; heat is the real killer. Some of the tapes were fine, but some had just fused into a block. At the time, I had no idea what to do with those, so we had to set them aside. But we managed to bake and clean about 25, with some help from Quantegy.

“It was like archaeology — first the tapes were baked, and then it was a slow process of unwinding them by hand, using paintbrushes and an anti-static lint Quantegy had recommended to clean the mould from the surface of the tape. We worked pretty much around the clock for a couple of weeks, but we managed to get those 25 done. They were all multitrack live recordings — Bob Marley Live at the Lyceum, at the Rainbow Theatre, at the Hammersmith Apollo, stuff like that. Rita Marley came back and listened to the finished results, and was very happy and quite emotional about it. I guess it could all have been lost for ever.

“I’ve actually worked out a way of getting the tapes in the worst condition to play, now. A guy came in off the street one day with a tape of a prominent African artist that wouldn’t play, and when I opened the box, the oxide was just falling off, as though the binding had completely dried out. I suggested to the owner that a lubricant might help, and said I could try soaking it in de-ionised water, but there was no guarantee it would work. The tape was completely unplayable as it was, though, so he had nothing to lose. I soaked the tape for about two hours — it absorbed water like a sponge at first — until I could see the outer layers beginning to peel away. It was a judgement call, as I didn’t want to leave it too long and cause it to swell. It took several more attempts before the water penetrated to the middle of the tape, and only then could I safely unwind it by hand without ripping the oxide off. And after that, it had to be baked six times before it was playable. It took about a month in all. But finally, it played — and it sounded absolutely fine.

“After that, I did the same for the master of Althea and Donna’s ‘Uptown Top Ranking’. That tape was the same, but having tried it once, I was more confident, and it worked. We’ll do that for anyone with badly fused tapes now, but we have to charge a lot for it — over a thousand pounds a tape in some cases — because it takes so many man-hours to get the tape to the point where you can transfer it, and it’s painstaking, careful work. Obviously, some people decide it’s not worth it.”

The September 2005 issue of Sound On Sound can be accessed here.

Amusing anecdote about tape baking! First time I visit this blog. We talk about pro tapes and reel to reels at audioexmachina.wordpress.com (link allowed here? thanks)

If you happen to step by there you’re welcome!